It starts with four to seven ivory-colored eggs nestled amongst fluffy gray down, hidden on the ground within the grasses of the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, of coastal Alaska. All along the coasts north into the Arctic Circle similar nests exist. As the eggs hatch the precocial young join the adults as they feed on the rich invertebrates and vegetation that flourish in the Arctic summer. As the days begin to shorten and the young birds’ feathers fill out, the Black Brant (Branta bernicula) slowly congregate in Izembek Lagoon on the eastern side of the Aleutian Islands. Soon over 130,000 Brant, along with other geese and waterfowl, will stage there in the fall. The Brant families feed on the rich eelgrass beds building up their fat and calorie reserves in preparation for the trip to come.

Sometime in November an intense low pressure system will push through the area and slide down the west coast of North America. This triggers the flight the birds are preparing for. En masse, most of the Brant families take off into the winds following the cold front. Using the gales following the storm, they are aided in their southern flight south to their wintering areas. Some will stop in Northern California others go as far as San Quintin Bay in Baja California. It is a non-stop flight over the open ocean, with some birds consuming over a third of their body weight and making it from Alaska to Baja in as little as 55 hours.

The Brant that stay here in Morro Bay are families that have established this area as their winter home for generations. It’s a great area to stay for up to five months feeding on the eelgrass and resting on the estuary. Through band readings, scientists have documented some families using our estuary for decades (Brant can live as long as 28 years). Provided they survive predators and hunter’s guns, mated pairs will stay together for life, resting and feeding together and migrating wing tip to wing tip, teaching their young the same routes to take.

Come springtime the Brant will slowly depart for their trip north. It’s a more leisurely journey along the coast with the Brant families stopping to rest and eat along the way. Morro Bay is an important stopover for birds from Baja to fuel up as most of the estuaries between here and there have been developed and eelgrass is scarce. By the time the Brant arrive back in their breeding areas in coastal Alaska, some birds will have covered over 11,00 miles in their round trip journey.

We are lucky to have these winter visitors but sometimes the estuary can be a busy place. If there is too much hunting or recreational boating occurring on the bay the birds will simply leave for the day, fly out to the ocean, and rest in large flocks offshore, unable to feed or rest in the sheltered environs of the estuary. So, if you are out in your kayaks, SUP or other watercraft be aware of the bird’s behavior. If they start chattering to each other as you approach and bunch together it’s an indication, they’re getting nervous about your proximity. If you truly care about them, try not to flush them from the non-hunting areas into the hunters’ guns waiting in the legal hunting zones.

The Brant are just one of the species of waterfowl that make our estuary such a special place, let’s all remember to give them their space and show them, and the other water birds we share this space with, a little respect for the effort they put out to get here.

A little more info about wintering Brant: The number of Brant wintering in Morro Bay has always fluctuated. From 1950 through 1966 counts averaged around 6,000 with a high of almost 12,000. The last time we had over 1000 brant in Morro Bay was in 2010, in 2015 we only had 116. This year, we had over 900.

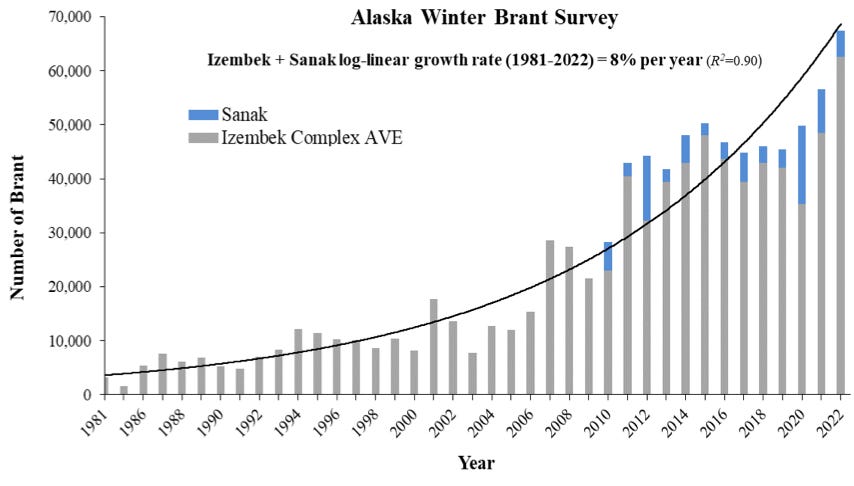

Weather, eelgrass abundance, and other factors can contribute to the declining numbers, but one factor seems to play an outsized role in the number of Brant migrating to their winter homes: climate change. Put simply, Brants are realizing that the Alaskan winters are not as harsh as before and the food supply in Izembek Lagoon is adequate, so they are staying up north and not making the journey. As the chart below illustrates, climate change can affect many things.

That’s what we’ll discuss in our next post.